The Jordan Valley settlements are perpetuating occupational violence, placing many Palestinians that work in agriculture outside Israeli labor law. The farmers depend on the Palestinians as agricultural products require pickers and packers, and the Palestinians depend on the farmers due to scarce employment opportunities in the region. But what about Palestinian agriculture? It is constantly shrinking due to low water quotas, which force Palestinian landowners to dry out their fields and work the settlement fields instead.

Workers only earn about ILS 80-100/day, when the daily pay for minimum wage work is ILS 233. They are employed without pay slips or social benefits, e.g., paid leave, sick leave, vacation pay or pension pay – and without job security. Some work 30 days a month, without days off, and some get injured and are then let go to take care of themselves, at their own expense.

Fear is in control here: attempts to question the employer’s instructions or absences due to holidays or family events are met with threats of termination. Any worker who dares to sue his employer in court to get his legal rights is then “blacklisted” by regional employers, and his family members lose their livelihood as well. The employers, for their part, know that the Jordan Valley offers no employment opportunities, and any worker sent home is quickly replaced by another who will agree to work under the same terms. This is what exploitation looks like. This is a population with no bargaining power who has no one intervening in their behalf.

In the coming days, we will publish the stories of five workers employed in Jordan Valley settlements. They are afraid to identify themselves and fear talking to others about their situation, so we are concealing their identities.

“Many children work in agriculture in the Jordan Valley settlements, and the employers welcome them with open arms”

Jahrir, 24, has been working since he was 12 years old in order to help provide for his household. His young age was not uncommon in the field. “Many children work in agriculture in the Jordan Valley settlements, and the employers welcome them with open arms because the children want to prove themselves and try harder than others.” These children do not get to finish school and their future is doomed.

Jahrir, 24, has been working since he was 12 years old in order to help provide for his household. His young age was not uncommon in the field. “Many children work in agriculture in the Jordan Valley settlements, and the employers welcome them with open arms because the children want to prove themselves and try harder than others.” These children do not get to finish school and their future is doomed.Jahrir works 30 days a month and earns 3,000 shekels. “If I take a day off on the weekend, I lose money that I need,” he says, “and still, the employer does not care whether I’m a good and dedicated worker or not.” he continues. “With one mistake, he’ll turn on me. One 10-minute prayer during the day is prohibited.” Jahrir talks with shame about his recent work accident, when he injured his leg: “the employer asked me: ‘why your leg and not your head?.’ How can you build a relationship like this? I paid out of my own pocket for medical treatment, stayed at home for four weeks until I recovered, and got 400 shekels for four sick days. That is what the employer thought I deserved.”

Every now and then, enforcement supervisors come to check on things among the Jordan Valley agricultural workers, Jahrir says, but the employers know when they’re scheduled to come and do a house cleaning. They get rid of any evidence of violating workers rights. They are proficient at it. And still, even though opportunities for fair and appropriate pay can be found some dozens of kilometers away from Jahrir’s home, he does not envy the Palestinian workers who work in Israel and earn 350-400 shekels a day—three to four times what Jahrir makes—and pities their agonies en route to earning a livelihood. “On a certain level, I’m lucky,” he says, looking away.

“We’re like tools in their eyes—work tools—but, a tool has an expiration date and we do not, and they treat us accordingly.”

Afaf, 34, has been working since she was 17 years old, but it is only during the past five years that she has been working in the settlements – packing and cleaning. “We’re like tools in their eyes—work tools—but a tool has an expiration date and we do not, and they treat us accordingly,” she says. The hourly pay is 10 shekels; there is no bathroom for workers, which forces the female workers to relieve themselves outdoors; and it is prohibited to pray during work. “Even during Ramadan days, no consideration is given to the fact that workers are fasting and require a meal before the fast starts and one after it ends,” she says, “all of our needs are dismissed for the employer’s needs.”

Afaf, 34, has been working since she was 17 years old, but it is only during the past five years that she has been working in the settlements – packing and cleaning. “We’re like tools in their eyes—work tools—but a tool has an expiration date and we do not, and they treat us accordingly,” she says. The hourly pay is 10 shekels; there is no bathroom for workers, which forces the female workers to relieve themselves outdoors; and it is prohibited to pray during work. “Even during Ramadan days, no consideration is given to the fact that workers are fasting and require a meal before the fast starts and one after it ends,” she says, “all of our needs are dismissed for the employer’s needs.”

Employers do not want to deal with the workers, and so they give the ‘Rais’ – a Palestinian who mediates between the workers and the employer – a check that includes all the wages. Even at this stage of the payment, many workers lose a part of their wages, as Raises turn to money changers to redeem the check and it is how an additional 10% disappears from the worker’s pay as commission to the money changer.

“If there is an electrical short or a problem with any machine,” Afaf says, “they don’t let the workers work and they don’t pay them for the lost hours, forcing them to swallow the damage.” A work tool has an expiration date, as mentioned, but workers do not.

“Worker lunch breaks take place on the bare ground and workers use cardboard as chairs and tables.”

Thamer, 44, has been working as a foreman at a packing facility in one of the settlements. “The workers’ lunch breaks take place on the bare ground,” he says, “and they use cardboard as chairs and tables.”

Thamer, 44, has been working as a foreman at a packing facility in one of the settlements. “The workers’ lunch breaks take place on the bare ground,” he says, “and they use cardboard as chairs and tables.”

“I know some workers earn 15-20 shekels for overtime, but I get paid 13 shekels per hour of overtime.” How much does overtime cost to an employer by law? –36.4 shekels for the first two hours.

Tahmer’s work, along with his abuse, is undocumented. The employer knows that no one will protest this pricing, and the state won’t come to ask any redundant questions.

At the end of the day, at least I get to keep my health,” he says. “There are plants in the Mishor Edumim and Ma’ale Efraim industrial areas where Palestinians are given better terms, but they are exposed to toxic chemicals, they do not have any protective gear, and they suffer from skin and respiratory problems.”

“If I were to ask for a day off, for any reason, the employer’s response would be: “no need to come—don’t show up,” meaning, “don’t come back again.”

Ali, 35, mainly works in date harvesting in the settlements, a key crop in the Jordan Valley region. “My workday in the settlements starts at 6 am and ends at 1:30 pm. I get 10 shekels per hour, and during the date picking season I work overtime for 15 to 20 shekels an hour.”

Ali, 35, mainly works in date harvesting in the settlements, a key crop in the Jordan Valley region. “My workday in the settlements starts at 6 am and ends at 1:30 pm. I get 10 shekels per hour, and during the date picking season I work overtime for 15 to 20 shekels an hour.”

The treatment of workers here is consistent, and the illegal pay goes hand in hand with avoiding responsibilities. “Two weeks ago,” Ali says, “a Palestinian worker fainted because of the sheer pressure he was under at work. When he came to and called the Israeli manager, the manager advised that he should take care of himself. When I injured my leg, the employer did not call an Israeli ambulance or arrange for my evacuation.” Ali, whose employment is undocumented, was unable to report a work accident and is required to pay ILS 1,500 out of pocket for medical insurance. His life experience as a settlement worker taught him that employers are blind and deaf to the needs of their workers, and the threat of dismissal is omnipresent. Each day can be his last day of work.

“If I were to ask for a day off on a certain day, for any reason, the employer’s response would be: ‘no need, don’t show up’, meaning, ‘don’t come back again.” Driven by the fear of losing his livelihood, Ali keeps working under any circumstances.

There is yet another component to this equation – the Rais. “The Palestinian contractor, called the Rais, brings me to the workplace and takes a cut of my pay. We depend on the Rais to bring us to work and pay our wages after he receives the money from the employer,” he says. It goes without saying that this dependency reduces monthly wages, making the employment even more abusive.

“The option of working in Israel is impossible for us because of the long drive. We’re also afraid of the monthly payment that needs to be made to a broker who sells the permits and of the stress of finding work every day to cover the permit costs,” Ali says. All of these considerations together, and each of them separately, lead him to forgo the idea. At least here, outside the world of labor laws, he knows his options.

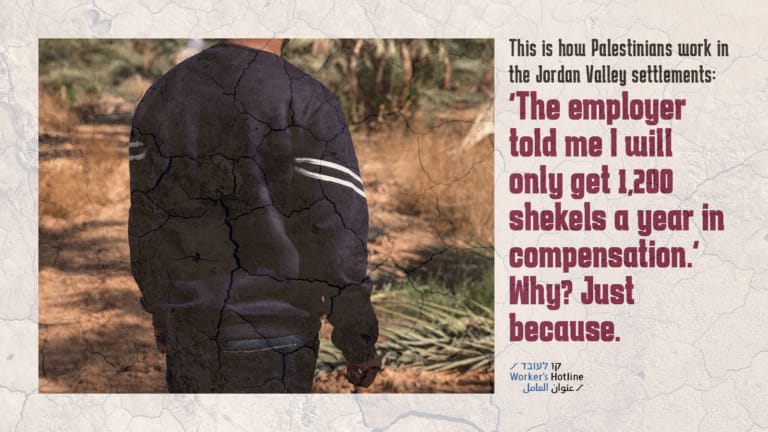

“The employer told me I will only get 1,200 shekels a year in compensation.” Why? Just because.

Ahmed, 41, has been working for an Israeli farmer in the Jordan Valley for over a decade from 6 am to 4 pm, and even after 6 pm during picking season. “I worked cultivating spices and lifted heavy boxes,” he says. “A few months ago, I felt sharp pains in my back. When I went to get checked, I discovered I have a hernia and a kidney problem. When I told my employer I cannot keep working, he told me I will only get 1,200 shekels as compensation for each work year.” Why? Just because.

Ahmed, 41, has been working for an Israeli farmer in the Jordan Valley for over a decade from 6 am to 4 pm, and even after 6 pm during picking season. “I worked cultivating spices and lifted heavy boxes,” he says. “A few months ago, I felt sharp pains in my back. When I went to get checked, I discovered I have a hernia and a kidney problem. When I told my employer I cannot keep working, he told me I will only get 1,200 shekels as compensation for each work year.” Why? Just because.

Not having any pay slips documenting his work or a work permit and getting paid in cash without the option of proving continuous employment, Ahmed hesitates in going to court: due to the Jordan Valley regulations that require Palestinians to deposit a guarantee if they don’t have preliminary evidence of employment, he is not off to a good start.

“There is a worker who sued his employer and then covered his face for three years so he won’t be identified, because a worker who sues is “blacklisted” in the settlements and nobody will pay him if he is identified,” he says. The employment of relatives is also jeopardized in this situation, as employers who got “burnt” by workers demanding their rights then issue a collective punishment against the worker’s relatives and family members, depriving them of job opportunities, in order to impose fear on workers.

In 2016, Ayelet Shaked, then acting as the Minister of Justice, received correspondences from Israeli farmers in the Jordan Valley. They claimed to be experiencing an “intifada of lawsuits” by Palestinian workers demanding their legal rights, thereby flooding the court system. In response, Shaked enacted a regulation which specifies that any lawsuit filed by a non-Israeli worker requires a guarantee deposit to secure the defendant’s expenses, as it is more difficult to charge expenses and/or use execution procedures against them. Shaked argued that she is acting to curb the false claims and reduce the overload on the court system, and that amending the regulation is within her powers.

Kav LaOved noted the expected damage to workers and petitioned, jointly with the Citizen’s Rights Union and the Adalla Center, against the regulations. In their petition, they argued that “the regulation constitutes an example of a discriminatory and dangerous secondary legislation that originates in pressures exerted by employer groups that seek to continue and breach the rights of their weak workers, undisturbed. It will change reality for hundreds of thousands of Israeli workers, who are employed in the most inferior and tough jobs, and who already suffer from underenforcement of their workplace rights.” In parallel, the claim of an “intifada of lawsuits” was checked and found to be fictitious.

The petition was denied. The Israeli High Court of Justice ruled that courts will not block the path of workers to court and will not have an overall demand in place to deposit a guarantee, but rather will balance between “a guarantee deposit or preliminary evidence” – meaning that an employee that can prove, in a preliminary fashion, that he has worked for an employer that violated his rights, may make his arguments without depositing a guarantee.

Over time, the regulations have made lawsuits even more difficult for impoverished workers, both Palestinians and labor migrants, who face routine, abusive employment.